The Cardioid Microphone

The standard stage and studio microphones obtainable almost anywhere are cardioid - they have a sensitivity contour that is heart shaped with the point smoothed off.

The directional pickup pattern is accomplished by controlling the extent to which the sound (pressure) waves get at both sides of the diaphragm so that sounds from some directions cancel out. By adjusting the ratio of absolute pressure (omni) to differential (figure-eight) responses, a wide range of directionalities can be obtained, so the mechanism used by the standard cardioid is also common to almost all conventional directional microphones.

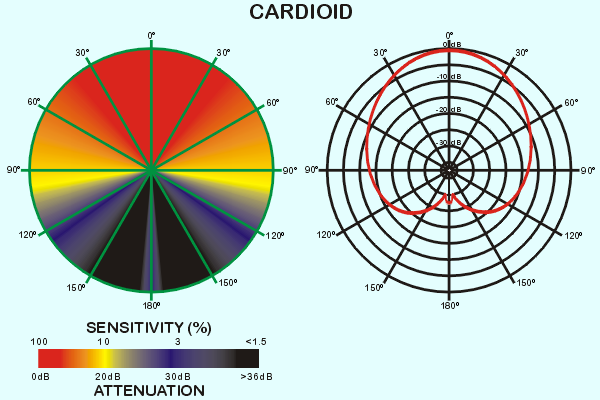

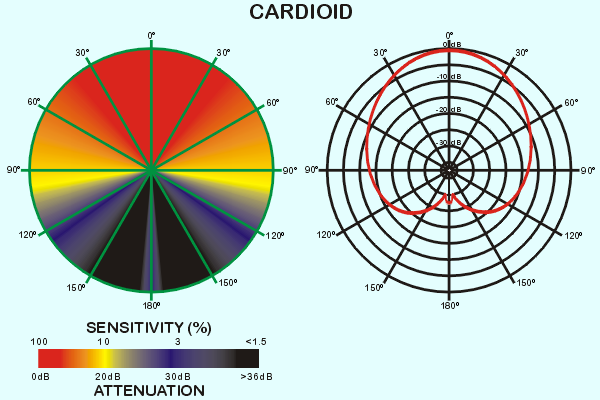

The field of maximum sensitivity of a standard cardioid microphone extends about 45° either side of the centreline, falling off progressively either side of this central 90° field. Sensitivity is at around 10 per cent of maximum at 90° either side and is extremely low behind the microphone - although there may be a narrow lobe of slightly increased sensitivity immediately behind the microphone.

This typical pickup pattern is the origin of the 90° angle between a pair of stereo microphones - the reduced sensitivity of each microphone in the centre of the field is compensated by both microphones picking up much the same signal. When the two signals are added together, the result is about the same as the maximum sensitivity of each microphone at the centre of its individual field.

Is important to remember that a directional microphone is not like the telephoto lens on your camera. It doesn't "zoom in" on sounds as some commentators frequently assert. It simply varies in its ability to ignore sounds from different directions. The camera can't photograph anything behind it, but very loud sound from behind the microphone will get recorded just the same as a quieter sound from directly in front - there's no such thing a "zero response" regardless of how directional the microphone is supposed to be.

A relatively rare type of cardioid microphone has a variable pickup pattern. Variable pickup pattern microphones use electronics to manipulate the signals from a pair of back-to-back diaphragms, allowing the pickup pattern to be selected by the user. Some allow selection of omni, figure-8 or cardioid pattern, and some have a continuously variable pattern.

Almost all variable pickup microphones are big studio mics. They tend to be expensive and fragile, and - particularly in the case of continuously variable mics - it's not likely the field recordist will have the peace and time to set them up optimally. They're interesting as a technology, but probably not very useful to us for wild soundscape recording.

The directional pickup pattern is accomplished by controlling the extent to which the sound (pressure) waves get at both sides of the diaphragm so that sounds from some directions cancel out. By adjusting the ratio of absolute pressure (omni) to differential (figure-eight) responses, a wide range of directionalities can be obtained, so the mechanism used by the standard cardioid is also common to almost all conventional directional microphones.

The field of maximum sensitivity of a standard cardioid microphone extends about 45° either side of the centreline, falling off progressively either side of this central 90° field. Sensitivity is at around 10 per cent of maximum at 90° either side and is extremely low behind the microphone - although there may be a narrow lobe of slightly increased sensitivity immediately behind the microphone.

This typical pickup pattern is the origin of the 90° angle between a pair of stereo microphones - the reduced sensitivity of each microphone in the centre of the field is compensated by both microphones picking up much the same signal. When the two signals are added together, the result is about the same as the maximum sensitivity of each microphone at the centre of its individual field.

Is important to remember that a directional microphone is not like the telephoto lens on your camera. It doesn't "zoom in" on sounds as some commentators frequently assert. It simply varies in its ability to ignore sounds from different directions. The camera can't photograph anything behind it, but very loud sound from behind the microphone will get recorded just the same as a quieter sound from directly in front - there's no such thing a "zero response" regardless of how directional the microphone is supposed to be.

A relatively rare type of cardioid microphone has a variable pickup pattern. Variable pickup pattern microphones use electronics to manipulate the signals from a pair of back-to-back diaphragms, allowing the pickup pattern to be selected by the user. Some allow selection of omni, figure-8 or cardioid pattern, and some have a continuously variable pattern.

Almost all variable pickup microphones are big studio mics. They tend to be expensive and fragile, and - particularly in the case of continuously variable mics - it's not likely the field recordist will have the peace and time to set them up optimally. They're interesting as a technology, but probably not very useful to us for wild soundscape recording.